Labour's epic rebrand

How the opposition repositioned in 10 short weeks

From salmon en croute to egg and chips

No-one saw it coming.

When Theresa May called an election in April 2017, it looked like a hopelessly unequal contest. On one side, you had the beleaguered leader of a divided party with no major donors and very few media allies. On the other, an experienced former home secretary, leading a party whose coffers were bulging and enjoying devoted support from four of the five top-selling newspapers in the UK. It was meant to be a rout.

Instead, Labour bust a phoenix move. It rose from the ashes to overturn the Conservatives’ huge 25-point poll lead and very nearly ousted Theresa May from Number 10.

So how did they do it?

Labour’s brand journey

Our take, based on all the available data, is that Labour pulled off a rebrand on an epic scale.

The extent of its repositioning is best captured in a piece of research carried out by The Guardian, which asked voters what each party would cook if it were hosting Come Dine With Me.

Before the campaign, the Labour brand was associated with salmon en croûte and craft beer, emblematic of a metropolitan Labour elite out of touch with its traditional roots. By the end, voters chose more down-to-earth meals like spaghetti bolognese or egg and chips.

In contrast, the Conservative brand was perceived “as resolutely upper-class as ever.” What was voters’ answer to the Come Dine With Me question? “They’d cook game pie, having shot the pheasant themselves.”

The election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader, two years ago, presaged a re-evaluation of Labour’s brand values in a way that can’t adequately be captured in a paragraph or two. Rebrands in political parties differ from orderly corporate rebrands in that they are often angry, divisive and conducted entirely in public. So it’s hard to capture the fundamental nature of the shift without sounding partisan. And this is not intended to be a partisan piece: it’s the analysis of an extraordinary event from a comms. viewpoint. Please bear that in mind as you read the following statement.

Essentially, the party abandoned its tainted “New Labour” brand and went back to “classic” Labour brand values.

As you’ll see, the data shows this repositioning was effective. People who had stopped supporting Labour now took a completely fresh look at the party.

Why did the public re-evaluate Labour’s brand?

Ask any brand manager: you can reposition all you want, the hard part is getting the public to change its mind. Once formed, perceptions are remarkably difficult to shift. So what made them shift this time around?

Certainly, the Conservatives’ unforced errors and ill-considered manifesto didn’t help them. Even so, these failings alone should not have destroyed a 25-point lead in the polls.

To understand what happened, let’s look back to January 2017. Internally, Labour was divided and had allowed its competitors to define its brand narrative. The Conservative-leaning press has been incontrovertibly hostile to Jeremy Corbyn ever since he became leader and that agenda often set the tone for the broadcast media. This relentless barrage of negative PR and the party’s own unforced blunders took their toll. Only 14% of people polled in January thought Jeremy Corbyn should be prime minister. Many saw the Labour leadership as comically inept, a grotesque, a clownish caricature.

But our analysis suggests the attacks on Labour by the press may have been overdone. It’s not just that fewer people buy newspapers each year, but also that they are less inclined to trust what they read.

So, when the legal requirement for ‘impartiality’ during election campaigns on UK broadcast news media kicked in, there was a huge mismatch between previous portrayals and what people were now seeing on TV, on social, and on the doorstep. In these circumstances, the public started to re-evaluate the Labour brand story. What the data shows is that most people were making up their mind which way to vote without even researching the Conservative offering. It strongly suggests the Labour Party captured the election agenda.

Source: Google trends

In the weeks before the election, people were actively researching Labour. And as any good marketer will tell you: consideration is the handmaiden of purchase.

When opportunity knocks, be ready

At the point where people were questioning the established narrative, Labour’s comms strategy had to be brilliant. It might never get another chance to capitalise on this rare opportunity.

Mindful of the chance of a snap election, Labour appointed KROW Communications last year to prepare for it. And the strategy they adopted was bold. Largely abandoning attempts to control individual messaging, it focused instead on a broad cause or movement. As the agency’s planning director put it: “If the campaign had stuck to one issue or leadership style, this could have been divisive. But by championing a cause, we could mobilise and unite. And the cause we chose was built from Corbyn, and Labour’s joint values of fairness, with an anti-establishment twist epitomised by the line: ‘For the many, not the few.”

So, rather than hammering home a few simple messages with vast ad spend – as the Conservatives were doing – the Labour campaign made a conscious decision to use its activist base. This enabled it to flex and twist around memes, humour, hope and (often savage) responses to events as the campaign unfolded. Labour’s earlier movement-building came to the fore at this point. The Conservative Party has under 150,000 members. The Labour party has over 500,000 members. Uniting activists around a cause and embracing the chaos of a multi-channel world, the Labour “movement” built networks like Red Labour, Corbyn Media Watch and others. These networks created and distributed User Generated Content (UGC) on a vast scale. The stream of content was non-stop, an ad-hoc steamroller of a social media machine that put Alastair Campbell’s fabled 1997 New Labour press operation to shame.

Activists even managed to get an anti-Conservative song to number 1 in the British music charts.

On official Labour channels, the party adopted a positive message of hope: refusing to attack the Conservatives (knowing that its unofficial activist army would take care of that, in spades). This strategy also helped reinforce lingering brand perceptions around the Conservative Party being ‘the nasty party’, because the Conservatives went very negative early on, repeatedly attacking Jeremy Corbyn and his team – often personally.

By contrast, Labour was offering a series of carefully focus-grouped product benefits (or manifesto promises). What’s more, the party deliberately targeted neglected market sectors by appealing to, attracting and converting a demographic largely abandoned in the last decade: the under 35s. Crucially, the party that captures the “hope for a better tomorrow” agenda is historically likely to win. And on that score, the Labour Party had the stage almost to themselves.

Labour activists were able to rally around this “hope” agenda and campaigned for the party in droves.

The data tells the story

Social media was the channel of choice for the Labour campaign. On virtually every available measure, Labour was stronger on social.

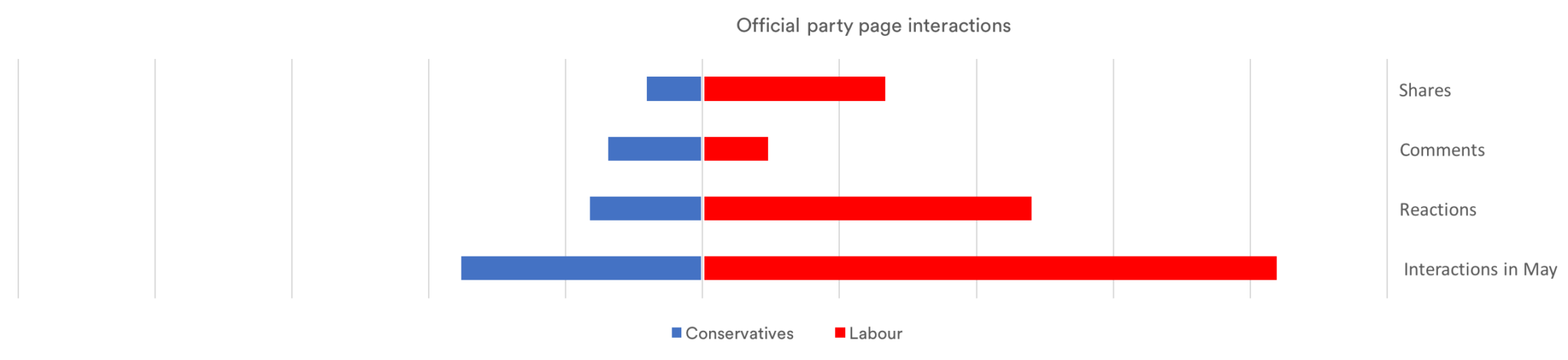

Source: socialbakers.com

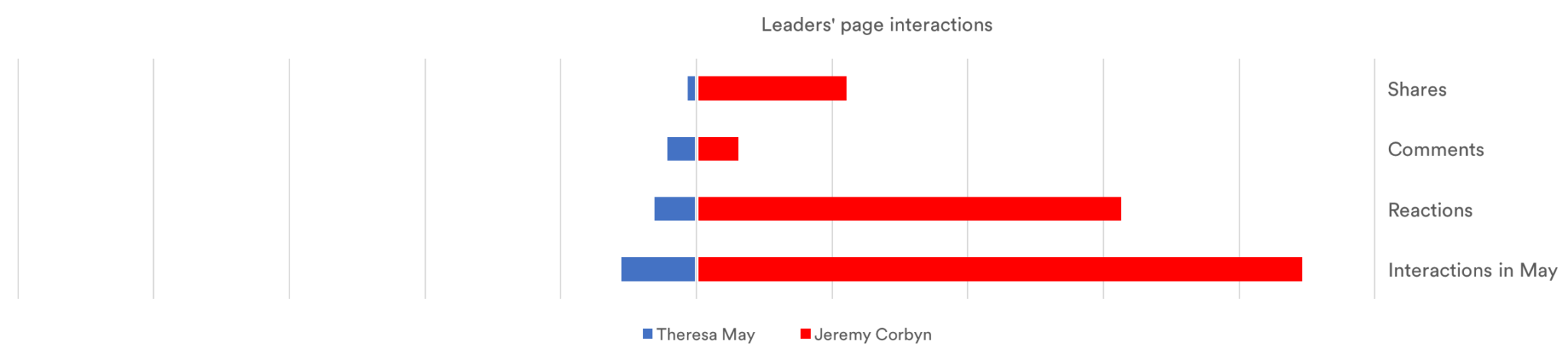

On Facebook, Labour activity on social media ran at over double the rate of the Conservatives. And over on the leaders’ pages, the same pattern was repeated. On almost every metric, Jeremy Corbyn was winning. And winning big.

Source: socialbakers.com

But there’s an odd datapoint here. Both the Conservatives and Theresa May overindex for comment interactions. To find out why, we visited the leaders’ pages. And as we dug into the content, we found a huge number of pro-Labour voices in play – arguing, debating, campaigning. To illustrate this, we took the latest few comments from the top post on each leader’s page, three days before polling day.

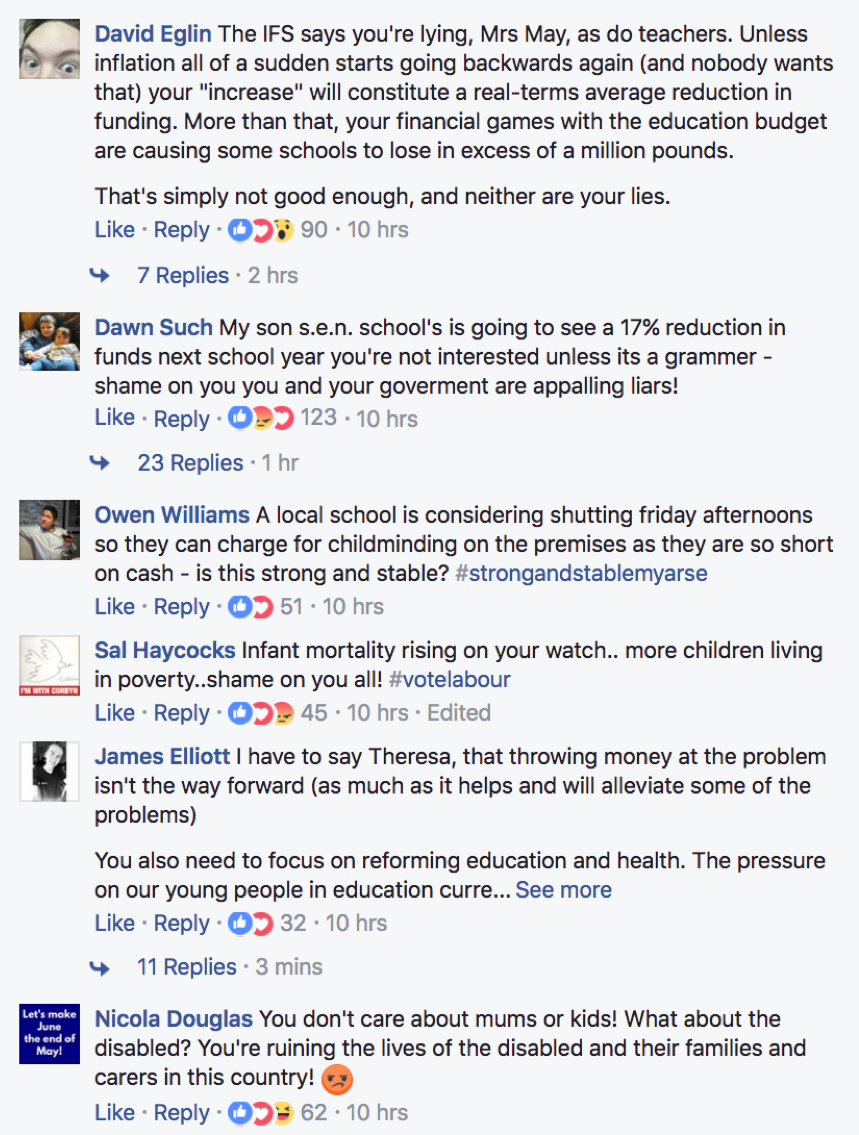

Here’s a sample from a post on Theresa May’s page, about a recent primary school visit.

That’s a top-line savaging right there.

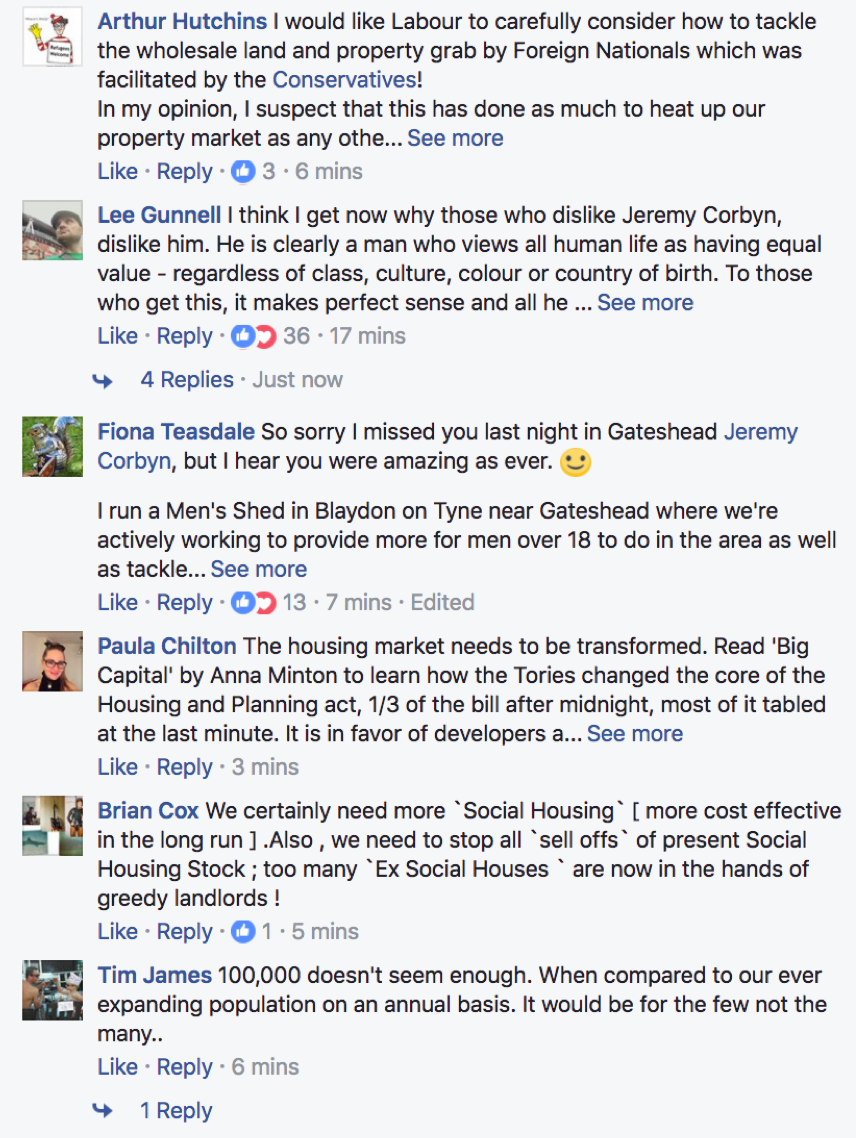

And here, by contrast, are the responses to a post on Corbyn’s page. It’s a paean of praise in comparison.

Side by side, it’s obvious just how one-sided the debate on social was. Even Conservative spending of £1.2m on Facebook ads couldn’t even the score.

The sheer volume and diversity of Labour voices bought it two of the most valuable commodities in the world of marketing: momentum and authenticity. This became the story of a plucky underdog “sticking it to the man”, buoyed by a groundswell of popular support.

So why didn’t Labour win?

To answer that, we just had to step away from our screens and pick up a newspaper.

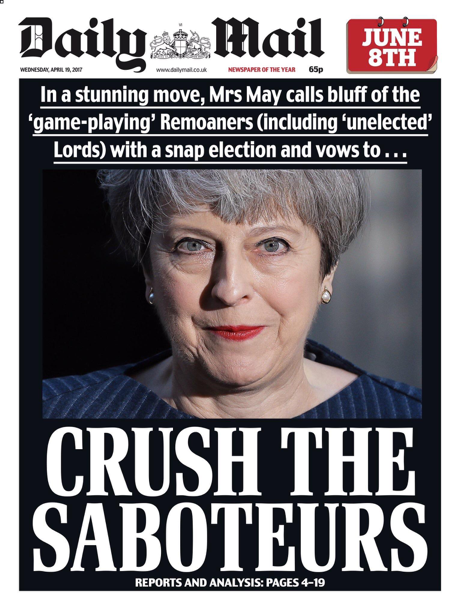

In the papers, the picture couldn’t have been more different.

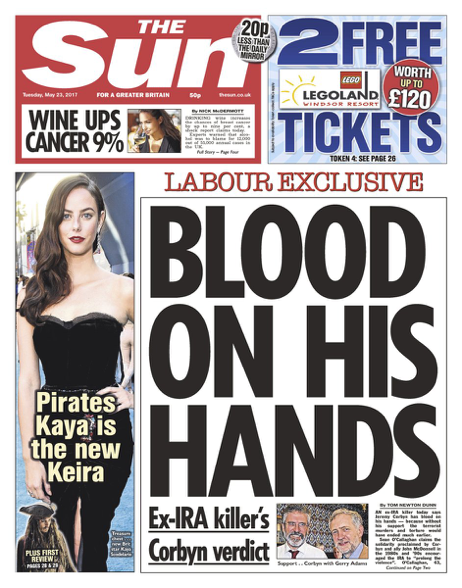

Ouch. To verify our impressions, we turned to the data. Loughborough University has been analysing newspaper coverage. It paints a pretty straightforward picture.

Balance of positive-to-negative newspaper items for each of the main parties:

Source: Loughborough University

A nation divided by its echo chambers?

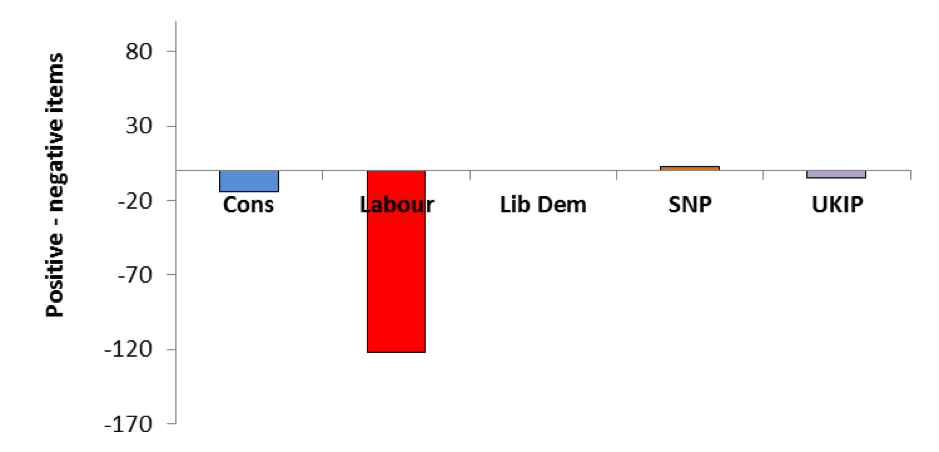

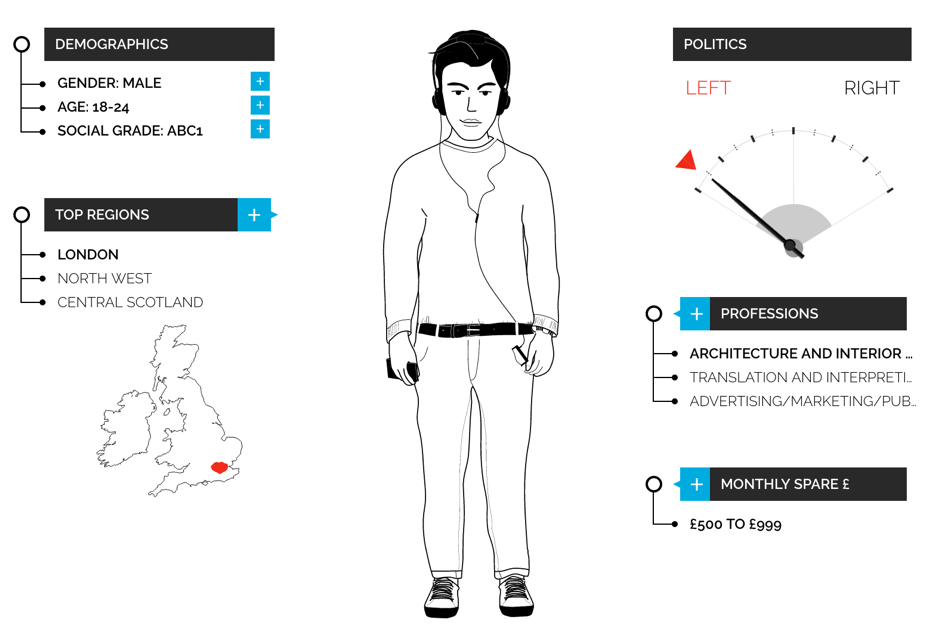

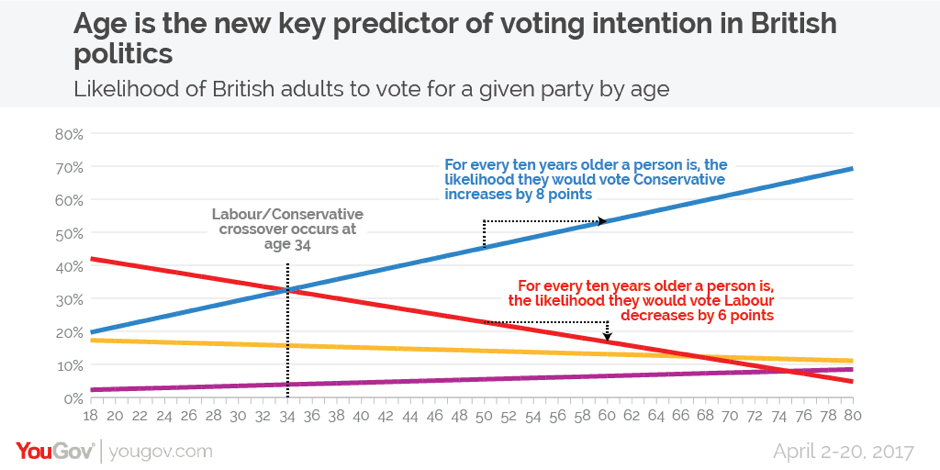

So, how could social media and the press deliver such different narratives? Ignoring media ownership for a moment, the other main dividing line seems to be age. Older people are generally more conservative and get more of their news from the papers. Younger people tend to lean more to the left and get their news from social media. Just compare ‘Users of Twitter’ with ‘Readers of the Daily Mail’, for example.

Source: YouGov

Source: YouGov

The difference is stark. People’s voting intentions were governed as much by their preferred media channel as by policies, issues and people. Statistically, older people don’t use social media to the extent younger people do, so we shouldn’t be surprised that they were less persuaded by Labour’s wave of ‘clicktivism’.

Source: YouGov

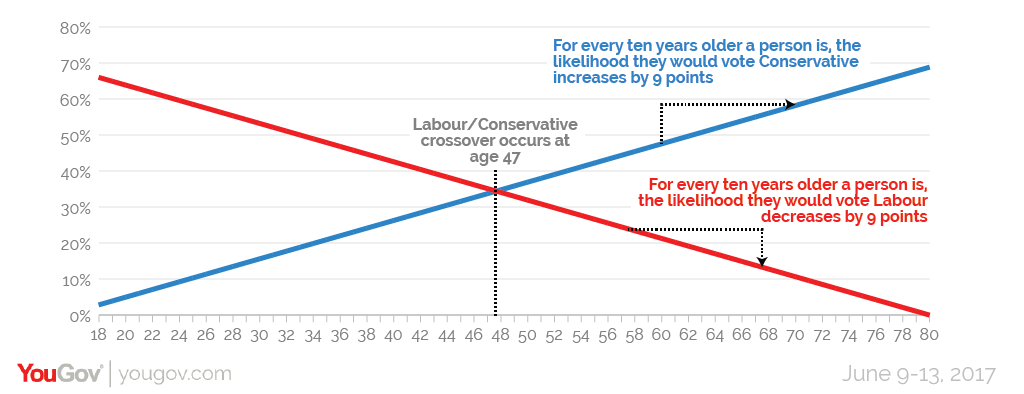

Even here, there was a substantial shift among middle-aged voters, with the crossover age from Labour to Conservative rising to 47, as this second graph shows from the end of the campaign.

Source: YouGov

Interestingly, the polarisation by age now seems even more pronounced, with the drop-off of Labour support increasing from 6 points per decade to 9 points per decade. Conservative support seems well entrenched with older voters. And older voters are still the demographic that turn out and vote, more than any other group.

The recipe for a new brand story

Of course, Labour didn’t actually win the general election and its brand story is obviously far from perfect. That said, it cannot be denied that it ran a blinder of a campaign. We’ve not seen many more profound brand turnarounds. In 10 weeks, the Labour Party’s brand was transformed from a laughing stock into a serious political contender.

This, then, is the recipe for a rapid and powerful brand repositioning:

- Identification of, and appeal to, neglected market segments

- Careful product research and formulation

- A disruptive, attention grabbing, proposition

- Great comms. strategy, composed of:

- Savvy use of the underexploited channels

- A multi-level content approach from high-end filmography to widespread amateur UGC

- A distributed network of brand advocates built over time

Together, these factors allowed the Labour Party to reshape consumer perceptions and push forward a narrative that has already changed the British political marketplace.

Repositioning your brand and getting consumers to accept your new brand story remains one of the hardest feats in comms. For that reason, viewing the outcome of #GE2017 through a brand management lens is strangely reassuring, regardless of your politics. It shows that turning around even the most terrible brand stories can be done.

What’s more, if you strip out the innovation of executing on social media at this scale, the fundamentals of persuasion haven’t changed. Our local hipster café may now offer locally sourced, artisanally griddled, duck eggs ensconced in a nest of hand-cut hickory-infused sweet potato chips: but it’s still basically egg and chips. Delivering the right message, to the right people, at the right time is a recipe as old as advertising itself. And that will never change.

To see some of our work in the FMCG, food, retail, health and wellness sectors, click here for case studies on how we’ve helped The Co-op, Atkins, Midcounties Co-op, Wagamama and many more.

Alternatively, if you’d like to learn more, give us a call on 0161 831 0831 and ask for Nicola or get in touch at hello@dinosaur.co.uk.

Also published on Medium.